(Part 1 of this series can be found here)

(Part 3 of this series can be found here)

Welcome, all, to a communications course that you aren’t getting a lick of college credit for! On the upside, you don’t need a $300 textbook and the reading materials are pretty light. Last time, we noted that this series will be limited (mostly) to the pre-electronic and pre-digital age, and discussed the idea that, for writers, the important part of studying long-distance communication is understanding:

- What kinds of messages can be sent,

- Who might send them,

- And how the needs, environments, and resources of the people using them affect their development and adoption.

We started by categorizing messages according to their complexity. Why? Because the resources and structures needed to send a message vary greatly depending upon whether the message is as simple as a “yes” or as complicated as a nuanced political alliance. Once we know how complex the message is, we can begin to figure out whether the environment will be a help or a hindrance, what technologies we can use to send the message, and, thus, who would be capable of utilizing them.

To that end, we separated long-distance communication into three distinct categories:

- Binary and pre-arranged signals, which are inflexible, pre-determined signals like emergency labels and smoke signals.

- Simple messages and coded communication, which reduce written or spoken language to a simpler, easy-to-transmit form.

- Complex, nuanced communications that have all the trappings of regular spoken or written language.

These categories aren’t hard and fast, of course. Certain technologies, depending upon how they’re used, can hop from one to the other. Your phone, for example, is mostly used for complex, nuanced communication but can also be used to check into a hotel room—a binary message.

The last article was focused on the first of these categories; binary and pre-arranged signals. Give the article a read, if you haven’t. Or, at least, read the introduction. Either way, here’s the summary: we concluded that binary and pre-arranged signals thrive on their simplicity. They can be used quickly by anyone, set up easily, and rarely suffer miscommunications. This makes them great for warnings, emergencies, and other utilitarian messages. But, their simplicity is also their downfall. They lack variety and flexibility, which makes them useless for conveying new information or saying anything that can’t be read off a list.

Luckily, we have other options.

Speaking, in Short: Simple Messages and Coded Communication

Eventually, the ideas humans communicate become too various or too complicated to properly convey through a pre-set system. This doesn’t require advanced political machinations. Even if we were to zoom back thousands of years, small tribes could need more accurate information than could be conveyed in a puff of smoke. A village could need to warn an ally that an enemy is coming… but may need to tell them what tribe, whether they’re armed, what direction they’re coming from, if there’re any survivors, and so many other variables that they would need a friggin’ encyclopedia-sized handbook to manage all the possible configurations. And, more importantly, they could need to send information that they don’t currently have. What if a tribe is attacking them with new weaponry? They may want to describe the weapons, which would be flat-out impossible with a pre-set signal.

To overcome this, it becomes necessary to create a system that has the flexibility of spoken or written language, but can be stored or quickly sent over long distances.

Arguably, this is where writing got started. In need of a way to record items being sold, stored, et cetera, merchants started making marks on clay and stone and whatever else they had on hand, with each of those marks representing specific items, numbers, and people. Those systems would, eventually, grow bigger and bigger until they came to represent the full breadth of complex language. We’ll be exploring that in greater depth in part three.

For now, the important part is that, in order to quickly send messages, people needed to distill spoken language into a transmittable form. That required breaking speech down into its constituent parts and coming up with an intelligible system that, at its core, was understood by translating it back to spoken or written language. While Morse Code is an obvious example of this sort of long-distance communication, I’ll throw a couple novel examples your way to show just how varied this technology can be… and, if I’m being honest, to keep you entertained.

Big Bars and Big Booms

Let’s start with the the Semaphore Telegraph. Invented in 1792 in France by Claude Chappe, these were big, windmill-like towers spaced five to twenty miles apart from each other, topped with three arms. Think a wide, oversized, rotating “H” whose lines can all spin independently. Chappe and his brother realized that someone could see the angle of these three arms from miles away, so he came up with a code system wherein different positions represented different letters of the alphabet or a separate 96-piece code system. When a message needed to be sent, they would position the arms to make the first letter. The closest station would see it and follow suit, and the next and the next. The first station would then input the next letter, and, after a while we’d have a complete message sent at a rate of 2-3 symbols per minute. Cumbersome as this system was, it was effective enough to give the French an advantage over their enemies that more than made up for their (then) shoddy military.

(Side note: the semaphore telegraph was also used in the very first telecommunication scam, as you can see in this video.)

But, if you want a more interesting example of coded messaging, you’ll need to hit up West Africa and grab a “talking drum.” (Yes, by the way, that’s a Wikipedia link. I’m not going to throw you six separate books you’ll need to pay to read.) The hourglass-shaped instrument went by as many names as there were groups using it, and had a motley of tight leather cords running between the drumheads which, when squeezed between the arm and the body, changed the pitch.

Oh, and it can mimic human speech. I should probably mention that.

See, many African languages are “tonal,” like Chinese, meaning that the pitch of a sound influences the meaning of the word. Given that a skilled drummer could manipulate pitch, volume, and rhythm with every strike of a talking drum, they could beat out a powerful representation of spoken language, even if it’s missing details about vowels or consonants. With that restriction, some words were a no-go or had to be translated into phrases. “Moon,” for example, was translated into “the Moon looks towards earth,” but the drummers often used that phrasing to provide extra context for a message.

The sounds from these drums could carry, distinctly, for up to five miles. That’s more than far enough for someone to hear them and relay the message. As a result, drummers could transmit a wide variety of messages at a rate of a hundred miles an hour. The tool put European colonialists through a loop because it gave West Africans a communication advantage over them and, despite being able to clearly hear the drums, the colonialists couldn’t figure out what they meant. So, like everything that kicked their ass, white colonialists tried to ban them.

Drumming Our Way Across the Cultural Divide

One way or the other, a system is created that allows people to communicate flexible messages over a wide distance. Do not, for a moment, underestimate the tactical and cultural value of this development. France’s semaphore telegraph system was one of the only advantages it had over its political rivals, but it was enough to keep them ahead of the game. Likewise, this communication can strengthen political organization and keep the pieces of a large kingdom moving in sync by coordinating basic day-to-day administrative and economic duties over long distances. Or, it can bridge the cultural gaps between clusters of human civilization by keeping them in constant communication and alerting them to festivals, rituals, or religious developments in neighboring communities.

This kind of connection has a powerful psychological affect on a people. How much closer would you feel to the neighboring village just by knowing what’s happening from day to day? It shrinks your world and connects you to the community at large.

This is reflected in the most important result of the change from inflexible to variable messaging: they no longer have to limit themselves to utilitarian messaging. African drum languages could be used for proverbs, storytelling, and nearly any kind of poetry. They represented their own form of oral literature and carried huge cultural value, meaning that this form of communication bounces between this bracket and complex communication. For further reading on that, I’d recommend researching “Griots,” the West African holders of oral tradition.

These kinds of coded systems have more benefits than just transmitting variable messages of middling-level complexity and closing cultural divides. First off, interference, while more likely than in binary/pre-arranged signals, is still unlikely. Environmental issues (like fog) are your biggest threats. And the fact that these systems are encoded means that enemies will have a hell of a time figuring out what these messages mean, even if they see and hear them clearly.

That encoding does pose a problem, however. The very act of encoding and decoding a message takes time beyond the time it takes to use whatever system you’re using to send a message, which makes coded communication slower than binary and pre-arranged signaling and introduces the possibility of miscommunication. That sounds obvious and unimportant… until you consider the possibility that they may need to send a complex message in the middle of an emergency.

On that note, these systems require either complex constructions or skilled users to operate properly, which greatly increases the value and importance of the objects or people necessary to use them. For a saboteur that means an easy, high-value target, while the layman is restricted from using these technologies almost entirely. Even with “simpler” systems like Morse Code and the semaphore telegraph, the bar for use is higher than with binary and pre-arranged messages, limiting who can use them.

That brings us to the greatest downside of coded communication: it isn’t egalitarian. I know: this seems strange, given that its greatest upside is bridging cultural divides. Still, given that either the structures or the people capable of using them are limited, coded communication naturally restricts itself to messages of public, cultural, or political importance. Individual civilians, no matter how wealthy, won’t be able to make any private use of them except in very extreme, unusual circumstances. In other words; don’t expect a message from grandpa by semaphore telegraph.

As a system of communication, coded messages are designed to send short, variable messages quickly over long distances, not to send long messages or capture the full breadth and nuance of human language. As a result, it comes off a little like Twitter; useful for what it’s designed for, but no replacement for long-form or nuanced language unless they develop an evolution of their form, like the talking drum’s potential for artistry.

In the next article, we’ll be making the jump to complex communication. For the most part, that means we’ll be discussing writing and delivery, and poking more fun at European colonists.

See you then, and happy writing!

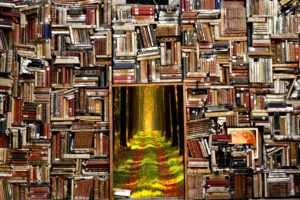

Featured image courtesy of Paul Brennan!